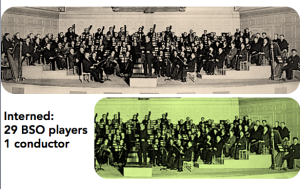

Nearly 100 years ago during World War I, a soap opera emerged in the U.S.’s elite symphony halls more sensational than anything Downton Abbey may offer. In Boston, the world-famous Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor, Karl Muck, and one-third of that orchestra were clapped in prison chains and hauled down to Georgia. They were classified as enemy aliens for their German ancestry and imprisoned with other elite musicians in the U.S. From there Muck orchestrated what experts at that time considered the greatest event in U.S. musical history.

Karl Muck was a Swiss citizen. He was at the top of his field and considered one of the best conductors and innovators of his time. This fact didn’t matter to his jailer, the 22 year-old J. Edgar Hoover, who was in charge of the Enemy Alien Registration department during World War I. Who puts a 22 year old in charge of Enemy Alien Registration?

After the fabric of our community is ripped apart, how do we rebuild? Peace treaties, judicial pronouncements, or civil agreements may stop a conflict, but they don’t heal wounds. We need people who can renewal into wounds in concrete ways. But how? If this were easy, we would all agree on how to live together and we do not.

One American virtue is innovation. The Latin root of “innovation” is innova, or “to renew.” Its first known use occurred when the Bible was translated into Latin. Psalm 51:10: Cor mundum crea in me Deus et spiritum rectum innova in visceribus meis “Create in me a clean heart, O Lord, and renew a right spirit within me.”

When renewing a company, a civic organization, or nation we need to start with a coalition of people with the character, courage, and curiosity to renew in ways that make more of all of us. That is, we need to renew not in any way, but in a way that allows for us to flourish. There are rules. There are standards. And there is also support and compassion to help people become their best.

Today, two American values conflict: connecting with humanity and protecting ourselves against inhumanity. When two values conflict, you learn which value holds the trump card. This debate happens continually in American history. How can we have a better outcome than in times past?

The miracle of life’s renewal and hope is found when people or communities with legitimate resentments do not harden their hearts and settle for “this is just how things are.” They remember that life has its terrors and also its sweetness. Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney called this remembering the “murderous and the marvelous.”

When writing my novel, The End of Innocence, I planned to write about a mysterious memorial at Harvard. Few can read it, as it’s in Latin. The modest plaque remembers Harvard students who fought for the Kaiser. In researching I stumbled into the story of Karl Muck, Boston’s brilliant conductor. I lost my heart to this man. He was not perfect, but had great talent, dignity, and joy. Muck’s story troubles the waters in the opening scene of my World War I novel.

Swiss conductor Karl Muck was understandably bitter at his treatment. He vowed he’d never conduct again in America. But in this prison near the Chickasaw battlefields, his friends in prison persuaded him to change his mind. His circumstances didn’t change, but perhaps he realized his friends and his own heart could use the encouragement. Significantly, he agreed to conduct Beethoven’s Eroica. a revolutionary work which expresses the idea that “Yes life can be terrible, but beyond the terror, there is renewal and even joy.”

Here is what an imprisoned eye-witness wrote about Karl Muck’s prison concert, given in the humble Appalachian foothills of northern Georgia:

“The mess-hall was packed with two thousand listeners. The orchestra numbered more than a hundred men, picked musicians all. The front benches were reserved for the army officers, the censors, a few doctors in uniform. Behind, wave upon wave, was the sea of the nameless, eager faces of the prisoners. …

In the moment of breathless silence preceding the first note it was as if an electric current had run through the entire unkempt audience in overalls and shirtsleeves, in heavy camp boots that seemed frozen to the floor. Muck waved his magic wand and jubilantly the “Eroica” rushed at us, lifted us on winds and carried us far away and above war and worry and barbed wire.

It is my conviction, and the belief of many others more qualified than I to speak with authority, that this last concert Karl Muck conducted in America was one of his greatest achievements and one of the greatest events in the musical life of the United States.”

When the baton was put down, Karl returned to his cell. The days were still long and freedom had not yet come to him. But he was not a prisoner in his mind or soul. His act was one of a man free to create beautiful music, even despite the horrors of life. The music held both the murderous and the marvelous in it. It always does. But, without words, only music, Muck invited those across the decades to remember the softness and joy of life, and to emerge from our prisons as free souls.